Idealistic practitioner aspirations of introducing qEEG and Neurofeedback into the VA Healthcare System are well-intentioned, but naive and wasted efforts

by John T. Hummer, Ph.D., BCN

I was trained as a Clinical Psychologist in the science-practitioner model in the mid-late 1980s, and would not make such a bold assertion unless years of experience and effort led me to this conclusion. I am recently retired after 27 years of full-time employment as a Psychologist in the VA Healthcare system, having worked in several facilities in three southeastern states. I tried to introduce new interventions into the VA system, and even wrote research proposals, all which met a dead end. The VA has no such interest. Its priorities include meeting congressional mandates, various performance measures, maintaining Joint Commission Accreditation, maintaining at least the minimum level of funding needed to sustain operations, and maintaining the status quo. Those who try to promote new ideas in a fixed monolithic system risk not only rejection, but damage to their professional reputations and career. I know, because I am one of them. In the VA, you go along to get along, get your work done on time without errors, maintain a sizeable workload, and don’t make waves or requests.

The VA is the largest healthcare provider in the United States, and one of the largest bureaucracies within the Federal Government. The structure is strictly hierarchical and top-down, based upon a traditional military-medical model of care. Though there have been recent initiatives to incorporate holistic health practices on a limited scale at each VA Hospital facility (termed ‘whole health’), the VA remains the most conservative of all agencies with regard to policies, rules, and regulations. Bureaucratic ‘red tape’ – originally intended as a method of slowing things down deliberately for careful review in the interest of prudence and safety – is the sine qua non of the VA.

All decisions pertaining to approval of mental health-related interventions are made by a select committee within the VA Central Office, employing a rigid set of criteria for assessing whether the evidence base is sufficiently rigorous to meet a standard ‘burden of proof’, along with demonstrated cost-effectiveness and facility/uniformity of training/supervision and implementation (termed a ‘roll-out’ initiative). Meeting the evidentiary standard or burden of proof usually means several large N, randomized studies involving some form of placebo control condition, as well as a no treatment control condition. Yet, there also seem to be some intangible aspects – perhaps a political element – involving a lobbying initiative to demonstrate that the new intervention is not only effective, but superior to and more cost-effective than the existing alternatives. Once interventions are accepted, they become ‘canonized’ – presumed safety and efficacy without being questioned or revisited/updated.

PE and CPT as ‘canonized’ VA interventions for PTSD

As a case in point, consider Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT: Resick,& Schnicke, 1993; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2016). They were accepted and rolled-out in the early millennium as the first line the VA’s first line psychological interventions for treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Since the time of the rollout on a large scale (throughout the VA), the empirical data have been mixed.

Two academically/bureaucratically-oriented assessments of the effectiveness of exposure therapies across mixed samples tend to favor PE and CPT. For example, Forman-Hoffman, and others, (2017) in a comparative effectiveness review prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) reviewed 207 published articles reporting on 193 studies involving various EBTs for treatment of PTSD. They rated Cognitive-Behavior Therapy-Exposure (CBT-Exposure) and CBT-Mixed treatments as having high strength of ‘evidence of benefit’ in reducing PTSD-related outcomes. Moderate strength of evidence of benefit was assigned to Cognitive Progressing Therapy and EMDR. CBT-exposure was deemed superior to relaxation in reducing PTSD related outcomes. They noted, however, that most studies did not describe methods used to systematically evaluate adverse event information (which could conceivably include re-traumatization and reasons for premature dropout) though insufficient evidence was found for ‘serious adverse effects’ akin to the type seen in experimental medications. Similarly, Curtois et. al (2017), convening an APA panel to offer guidelines for treatment of PTSD, strongly recommended CBT, CPT, and Prolonged Exposure Therapy, and conditionally recommended EMDR for adult patients with PTSD.

By contrast, Steenkemp et. al. (2015) conducted a metanalysis of the most methodologically rigorous studies involving veteran samples that utilized PE, CPT, and non-exposure control conditions such as Meditation. While PE and CPT outperformed waiting list and treatment-as-usual controls, an average of 60% of participants attained ‘clinically meaningful’ symptom improvement, defined as an average 10 to 12 point decrease in CAPS interview total score, and/or on self-report symptom measures. Average post-treatment scores for PE and CPT remained at or above threshold for PTSD diagnosis in at least 2/3 of the cases. In essence, ‘you are not quite as bad as before but you still have PTSD’ was the outcome for most veterans participating in the studies. Moreover, PE and CPT were only marginally superior to non-exposure-based trauma interventions (e.g. mindfulness/meditation). What was not given sufficient emphasis across the various studies was the extent of, and reasons for, the high number of non-responders and dropouts from these interventions, seemingly at odds with the ‘first, do no harm’ aspect of the Socratic oath.

Jay Gunkelman, a world-renowned medical EEG expert, has commented that up to 1/3 of patients with PTSD may have a ‘Beta Spindling’ EEG phenotype (see Johnstone, Gunkelman, & Lunt, 2010, for QEEG phenotypes based on raw EEG patterns), one which does not necessarily conform to the expected habituation and extinction response espoused by conventional exposure based methods. Individuals with the Beta spindling phenotype, often with obsessional features and high levels of trait anxiety, may sustain persistently high levels of arousal in response to confrontation without the expected habituation/extinction response, putting them at elevated risk for re-traumatization and/or dropout. This observation by a world-renowned QEEG expert merits further inquiry, and could potentially help to explain the partially successful outcomes among completers of PE and CPT, an issue which heretofore, has not been given due its due level of scrutiny.

Writer’s clinical experience is consistent with Gunkelman’s empirical observation. A sizeable proportion of individuals who undergo PE and CPT dropout prematurely. Among treatment completers, there is a consistent subgroup that reports having experienced retraumatization, and ensuring anger and self-blame for having trusted the therapist (who reassured them that PE or CPT would ‘cure’ their PTSD) and now being in worse condition than before undergoing the intervention. Yet, the VA keeps itself inoculated from any such criticisms, because few therapists or patients make formal complaints, and even when they do, these complaints never seem to reach the VA Central Office.

VA Rejection of Biofeedback for inclusion as an Effective Evidence-Based Intervention for PTSD

Few neurofeedback practitioners would question the effectiveness of biofeedback, particularly well-replicated interventions such as Heart Rate variability. Biofeedback research has established an association between chronic sympathetic hyperarousal related to post-traumatic stress and cardiovascular disease risk factors (Buckley & Kaloupek, 2001; Kibler, 2009), particularly among veterans diagnosed with PTSD (Orr, Metzger, Lasko, Macklin, Peri, & Pitman, 2000; Orr, Meyerhoff, Edwards, & Pitman, 1998).

Findings that persistently elevated heart rate and attenuated heart rate variability in response to chronic and situational stress tends to be characteristic of, and even predictive of post-deployment PTSD (Nagpal, Gleichauf, & Ginsberg, J.P., 2013; Chalmers, Quintana, Abbott, & Kemp, 2014; Dennis, Dedert, Van Voorhees, & Beckham, 2016; Pyne et. al., 2016) has led biofeedback practitioners to increasingly utilize heart rate variability/coherence training in veterans to help them learn to balance sympathetic and parasympathetic activity (e.g. Lande, Williams, Francis, Gragnani, Morin, et. al., 2010; Tan, Wang, & Ginsberg, 2013; Tan, Dao, Farmer, Sutherland, & Gervitz, 2011; Wahbeh and Oken, 2013; Lake, 2015; White, Groeneveld, Tittle, Bolhuis, Martin, Royer, and Fotuhi, 2017). Breathing retraining techniques have also been incorporated as an adjunct in some studies to aid in reduction of PTSD symptoms (Polak, Witteveen, Denys, & Olff, 2015).

Despite the promising and replicated findings of many individual studies, Biofeedback in general and HRV in specific have not been recommended for inclusion in the management of posttraumatic stress in the VA or DOD (see Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder, 2017), purportedly because it has not met the ‘burden of evidence’ required by most VA/DOD publications. Similarly, Neurofeedback has not officially been accepted by the VA system, even though it is being used experimentally by the DOD (Thatcher, personal communication, 2012; Othmer, 2012), which keeps its findings proprietary as private intellectual property.

SBG: A ‘medical’ intervention for PTSD recently approved for limited (provisional) use by VA.

With regard to interventions currently under VA review, one might even wonder whether or not a bias exists in favor of medical interventions. A case in point is Stellate Ganglion Block (SGB) to ameliorate/manage PTSD symptoms, which gained widespread note following a CBS 60 minutes segment by Bill Whitaker aired on June 16th, 2019. SGB has been used by interventional pain specialists since the 1930s to manage chronic pain conditions involving sympathetic nervous system overactivity, such as regional sympathetic pain syndrome, Reynaud’s disease, hot flashes and nocturnal awakenings experienced by breast cancer survivors and women with severe menopausal symptoms. Under fluoroscopy, analgesic medication is injected into the right side of the neck into a neuron bundle of neurons positioned along the spine (Stellate Ganglion), which is readily identifiable in approximately 80 percent of humans. While complications are rare, they are quite serious. There is the risk of injecting into the bloodstream by puncturing an artery or a vein. If anticoagulant medications and supplements are not discontinued for up to a week pre-procedure, inner bleeding could damage nerves and even the spinal cord. There is also the possibility of paradoxical rebound pain among individuals with developmental trauma with histories of dissociative symptoms (Bourne & Hefland, 2017).

Eugene Lipov, M.D., a Russian emigre and researcher authored/coauthored preliminary case studies involving use of SBG in treatment post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans (totaling 27 individuals across the studies); see Lipov, et. al., 2009; 2012; 2018). Sean Mulvaney, M.D., featured in the CBS segment, was principal investigator of a study at Walter Reed Hospital, where 166 Special Forces service personnel were administered 2 SGB injections, with a reported 70 to 75 percent symptom reduction as assessed via self-report measures such as the PCL-M. The primary methodological critique was the lack of an adequate (placebo) control group and randomized design (Mulvaney, Lynch, Hickey, Rahman-Rawlins, Schroeder, Kane, & Lipov (2014).

A study replication that included randomized double blind research design involving an SGB group and saline placebo injection control group was conducted at the San Diego Naval Hospital (Hanling, Hickey, Lesnik et. al., 2016; Hanling, et. al., 2017) The researchers reportedly replicated the procedures described in the preceding studies, with respect to injection site and dosage of the analgesics provided. Contrary to the earlier studies, the researchers reported finding no statistically significant differences on PTSD symptom measures between the conditions, thereby failing to replicate the findings of the earlier studies.

Lipov (2017) took issue with the findings of the randomized controlled study on methodological grounds. He noted that the experimental group was approximately twice the size of the control group, hence lack of equivalent group sizes. Lipov contended that procedures used in the RCT differed from those of earlier studies with regard to exact site of injection (C6, instead the junction separating C6 and C7), and noted that a much lower dose of the active analgesic medication was used in the RCT study. There were also significant differences between participants. In the Walter Reed study, the participants were Special Forces who tended to minimize PTSD symptoms, but upon learning of the magical results of earlier research, may have exaggerated PTSD symptoms to get into the study, and then minimized PTSD symptoms following treatment in an effort to get back to duty ASAP. In the San Diego Naval Hospital Study, a large number of participants were part-timers who were in the process of seeking service-related connection benefits for PTSD, and may have had a vested interest in maintaining their PTSD symptoms at a higher level. In both cases, therefore, data may have been skewed because of situational constraints and pressures. None of the studies placed emphasis upon dropouts or non-responders, nor did evaluation of potential side effects play an important role.

The results of a 3 year multisite study sponsored by the U.S. Army were recently published (Omstead, Bartosek, et. al., 2020). Using a random design and sham (placebo) control condition, 108 study completers showed at least a 10 point reduction on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, Version 5 (CAPS-5) from baseline to 8 week follow up. Apparently, the VA has allowed SBG to be used experimentally/provisionally at 10 VA facilities, but the only actual mention of this is on Sean Mulvaney’s website where he lists the facilities (https://sgb4ptsd.com/pageva). Until the CBS 60 minutes segment was broadcast, there was never any mention of this, at least through the VA facility writer worked at.

Empirical Status of Neurofeedback in the treatment of PTSD

There have been a number of small N neurofeedback studies evaluating the effectiveness of neurofeedback with PTSD, involving civilian and veteran samples. PTSD is of special significance in the VA, because it is probably the single most serious psychiatric condition afflicting the veteran population, with multiple comorbidities (depression, anxiety, chronic pain, addiction, propensity for negative behavioral consequences including partner and family violence, job loss, aggressive outbursts involving risk of harm toward others and above-average risk of incarceration; increased risk of suicide.) Service-related PTSD conditions recognized by the VA are combat-related PTSD, PTSD secondary to military sexual trauma, and PTSD secondary to other stressors (e.g. polytrauma involving bodily injury and TBI from blast injuries, impact injuries, witnessing of horrendous events, etc.). The following review relates to neurofeedback used in veteran samples.

Neurofeedback approaches span fast wave training (Beta/SMR amplitude uptraining), slow-wave (Alpha-Theta) training; Infraslow/Infralow training, Z score (cortical) surface training, S-Loreta region of interest training, and stimulation-based approaches (e.g. Audiovisual Entrainment, Alpha-Stim, LENS, Neurofield, Microtesla, RESET which uses individually attuned auditory binaural beats.) For overviews of neurofeedback research and training approaches for PTSD, see Wigton & Krigbaum, 2015; Bell, 2017; Butt, Espinal, Aupperle, Nikulina, & Stewart, 2020; and Steingrimsson, Bilonic, Ekelund, Larson, Stadig, Svensson, Vukovic, Warenberg, Wrede, & Bernhardsson, 2020).

It is a sad irony that the very first trials of combined biofeedback and neurofeedback (that stimulated so much subsequent research and clinical work) originated within the VA system, but were never formally adopted for ongoing use with veterans by the VA Central Office. Eugene Peniston and Paul Kulkowsky reported the first study to utilize a combination of biofeedback (e.g. handwarming, autogenic training, progressive muscle relaxation) and neurofeedback (reinforcement of Alpha/Theta waves, also known as Alpha-Theta neurofeedback) to treat veterans in residential treatment for alcoholism at a VA facility in Colorado, to augment ‘treatment as usual’ (e.g. conventional 12 step approaches, group therapy, medication management). Outcome data indicated that the experimental group (receiving biofeedback/neurofeedback in addition to treatment as usual) showed 70% greater success in preventing relapse than did the ‘treatment as usual’ control approach. The Peniston ‘Alpha-Theta’ protocol has been well-replicated in successfully treating addictive disorders at a number of addictions treatment programs in North America (e.g. see Trudeau, 2000; Scott et. al., 2004).

Peniston & Kulkosky (1991) extended the alpha-theta protocol for use as an alternative treatment for combat servicemen with PTSD. They recruited 29 Vietnam veterans suffering from chronic war-related PTSD, including frequent anxiety-evoking nightmares and flashbacks. In comparison to 14 control group participants (who received psychiatric medications including tricyclic anti-depressants, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics, the 15 ‘experimental group’ participants received biofeedback training (to reduce sympathetic arousal), followed by thirty sessions of alpha-theta neurofeedback (each session lasting 30-minutes). Neurofeedback sessions significantly reduced their PTSD symptomatology, although the intervention was emotionally intense (abreactions) for many of the veterans, as well as the primary therapist (Kulowsky). A follow-up 30 months later indicated that all of the control participants (medication treatment alone) had experienced a recurrence of PTSD symptoms (including flashbacks), whereas 20% (3 of 15) of the experimental (biofeedback/neurofeedback) participants reported a recurrence of flashbacks.

In a similar study with dually-diagnosed veterans (PTSD and addictions) Peniston, Marrinan, Deming and Kulkosky (1993) similarly found that alpha-theta brainwave training significantly reduced anxiety provoking nightmares/flashbacks. Again, only 20% of veterans (4 of 20) who underwent the alpha-theta protocol reported relapse of alcohol/substance use. Many participants reported that traumatic recollections were no longer significantly anxiety-provoking during and after the biofeedback/neurofeedback treatment.

As part of a military-related stress reduction program, Putnam (2008) showed a relaxation video (induction) followed by one-channel Alpha (and low Beta) amplitude enhancement training at site Pz (using a means of visual feedback) in a sample of 77 Army Reservists. He found that increases in alpha amplitudes (eyes open training) were associated with reports of increases in energy level, positive mood, reduced arousal, and in some cases reduced vigilance.

As doctoral dissertation research, Smith (2008) conducted a study of 10 military veterans with PTSD-induced depression and decreased levels of attention. After 30 sessions of neurofeedback (alpha-theta) training, all participants showed a significant and large-reduction in PTSD and depression symptoms, as well as an increase in attention levels.

More recently, the alpha-theta protocol was used successfully cross-culturally in a randomized study of soldiers with PTSD conducted by investigators in Iran (Noohi, Miraghaie, Arabi, & Nooripour, 2017). Similarly, Rastegar et. al. (2016), at the Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences in Tehran, Iran, reported the results of a study using Alpha-Theta training with 15 hospitalized war veterans suffering from PTSD, as compared to 15 hospitalized controls (no neurofeedback). The veterans were drawn from psychiatric hospitals in the cities of Sadr (a suburb of Baghdad, Iraq), Delaram (a town near Kabul, Afganistan), and Parsa (a city near Nepal, India). According to the authors, Alpha-Theta neurofeedback significantly reduced commission errors, omission errors, and reaction times on a Continuous Performance Test (CPT), a test of sustained attention.

Nelson and Esty (2012) utilized the Flexyx Neurotherapy System (Flexyx is the precursor of the Low Energy Neurofeedback System or LENS; both developed by Len Ochs, PhD.) to treat seven OIF/OEF (Iraq/Afganistan) veterans with comorbid PTSD/TBI conditions, all of whom had failed to benefit from standard comprehensive rehabilitation and standard medication treatments. Five of the veteran completed a full course (22-25 sessions) of Flexyx , demonstrating statistically significant ( p < .05) pre-treatment to post-treatment symptom reductions on the Neurobehavioral Functioning Inventory (e.g. depression, somatic complaints, memory and attention, communication, and motor issues, but not aggression p = .14). These five veterans also showed improvements on a PTSD symptom scale on re-experiencing and avoidance symptoms, approaching significant on hyperarousal (p = .06). Given the small sample size, these were impressive findings. The remaining two veterans discontinued treatment 13 and 17 sessions respectively, and reportedly experienced substantial symptom reduction, but post treatment data were unavailable.

Brenner (2011) reviewed neuroimaging and neuropsychological data with regard to PTSD and traumatic brain injury (TBI) among veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Focusing specifically on PTSD research, Brenner concluded that neurobiological activation influences functioning. He noted that chronic activation of (or alteration to) structures in the limbic system and prefrontal cortex is detrimental to longer-term physical and mental well-being. Reduced hippocampal volume and other premorbid neurobiological risk factors (from exposure to developmental and pre-military stressors) contribute to the development of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder.

Espousing a ‘dysregulation’ model of PTSD, Othmer (2010) reported the effectiveness of Infra Low Frequency (ILF: .05 Hz and below) as an efficient means of renormalizing the functional connectivity of resting state neural networks. He cited programs at Camp Pendleton and five other military bases involving several hundred trainees where neurofeedback is being utilized. Reportedly, 25% of trainees undergoing ILF obtain substantial symptom relief for all of their PTSD symptoms within 10 sessions, while 50% respond at a more moderate rate, and 25% respond slowly or not at all (intractable non-responders estimated at 5%). Because the raw and aggregate data are proprietary (intellectual property of the Department of Defense), Othmer presented a series of graphic illustrations showing the frequency of symptom reductions (across various groups of symptoms). The authors opined that whereas EEG neurofeedback is not yet considered an evidence based treatment for PTSD, the results of the ILF training would appear superior to all prior findings for PTSD, while cautioning that the methodology used in the military studies needs to be evaluated independently via formal research before it can be offered on a broader scale to service personnel. Benson & Ladou (2016) and Dahl (2016) further described the successful use if IFL therapy in case studies with veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

McReynold, Bell, & Lincourt (2017) reported a study of 20 veterans who received 20 to 40 training sessions of two-channel Z score neurofeedback, and demonstrated improvements on several scales on an auditory/visual continuous performance test. As one of a small number of fMRI neurofeedback studies involving PTSD to date, Gerin et. al. (2016) examined the effect of amygdala-targeted neurofeedback training involving three combat veterans suffering from chronic PTSD. Two of the veterans were reported to show clinically significantly improvements in PTSD symptomatology while the third veteran had a lesser degree of symptom reduction. Examination of the resting-state functional connectivity patterns suggested a trend toward normalization of brain connectivity, consistent with symptom improvements

Foster and Thatcher (2014) reported preliminary findings on 16 veterans from an ongoing study of combat veterans with comorbid PTSD and mTBI. They used the Neuroguide symptom checklist, and three-dimensional LORETA (Low Resolution Tomagrapy)-based 19-channel Z score Neurofeedback, training multiple neural networks. Dysfunctional neural networks implicated in PTSD include the Default Mode Network (DFN), Salience Network, and Executive Control Network (Bluhm et. al. 2009; Menon, 2015; Lanius et. al., 2015). Foster and Thatcher reported normalization of the PTSD-affected neural networks trained as well as a rapid resolution of PTSD symptoms, using protocols customized to the individual aspects and needs of the veteran.

Lindenfeld, Rozelle, Soutar, Hummer, & Sutherland (2019a) reported a significant symptom reduction on the CAPS-5 interview, together with evidence of reorganization toward normalization on the qEEG after 4 sessions of from baseline to RESET therapy in 8 combat veterans with uncomplicated PTSD. S-LORETA analysis of the data of one veteran in the sample who was court-ordered to treatment (Veterans Court) indicated significant improvement in the region of interest, along with a cessation of physically aggressive/abusive behavior, and increased emotional and physical intimacy (Lindenfeld, Rozelle, Hummer, Sutherland, & Miller (2019b).

Rex Cannon, Ph.D., the Editor of the Journal, Neuroregulation, reported successful treatment of PTSD among both veterans and civilians with approximately 20 sessions S-LORETA-guided live Z score training (full cap) targeting a Region of Interest (ROI) principally involving the precuneus (personal communication, 2019), though his findings had not been submitted for publication at that time.

Personal Experiences Expousing New Interventions in the VA

I did part of my internship at Charleston, SC, VA Hospital in 1991-1992. I recall having been shown the biofeedback lab at Charleston VA, operated by a biofeedback therapist named Joe. It was full of large, bulky, and intimidating-looking 1970s and 1980s analog equipment, reminiscent of a bygone era when funding of promising interventions was supported to help ailing and vocal Vietnam Veterans with PTSD in dire need.

I began my VA career as a Clinical Psychologist in July, 1994, at Bay Pines VA Hospital In Bay Pines Florida. It was the ‘decade of the brain’, and I had trained in Neuropsychology via a 2 year postdoc at the Institute of Psychiatry at Medical University of South Carolina. My only exposure to qEEG/Neurofeedback had been a booth at the National Academy of Neuropsychology meeting in 1992 in Pittsburgh. A Psychology Intern colleague was persuading my mentor to consider qEEG because of its accuracy. I recall my mentor dismissing it as ‘an expensive technology with not a lot of research to support it.’ In 1995, a Psychology Intern I was helping to train mentioned and briefly described EMDR to me, which I dismissed as hard to believe, and possibly a fad (with little to no understanding of EMDR).

I was far more open to EMDR after I survived a motor vehicle accident in July, 1991, involving the roller of an SUV, of which I was the driver. My wife, two sons, and mother were heading out of town on I-75 just north of Tampa when the camper-trailer we were hauling began swaying out of control, and I made a fateful decision to pull onto a soft shoulder, causing the rollover accident.

I sustained a concussion, and permanent injuries to my cervical spine with chronic pain as a reminder. I was demoralized and burdened with guilt, and experiencing visual flashbacks in slow motion, nightmares of driving a vehicle losing control and crashing that caused me to awaken in dread and panic, and fear of even riding as a passenger in a vehicle.

My ex-wife, Vicki, a licensed clinical social worker and child psychotherapist, referred me to a very experienced social work colleague who did EMDR (Shapiro, 2008) . I was so distressed that I was willing to try anything, yet skeptical. That first session of EMDR provided so much relief (although I needed two brief courses of EMDR to recover) that I became determined to get trained in it, and use it to help others. Once trained, I wanted to tell the world about this magical new therapy.

Veterans were open to it, but commented on its weirdness. I managed to get VA to purchase a light bar, and started using it with clients. One of them called it, “The flashing blue light special.” I started telling my colleagues about it where ever I could. (A small number of mental health staff were interested in it, or had undergone training). But a group who considered themselves the ‘trauma experts’ were not only dismissive, but seemed to have a preconceived antipathy toward EMDR (It turned out that these were PE and CPT proponents, who viewed EMDR as unscientific, faddish, and a threat to their turf). From 2002 to 2007, I attended EMDR trainings, peer support groups, and arranged a weekly small peer support group, but by 2004/2005, it had fizzled out. And in 2007, the Chief of Mental Health became convinced (after attending a training by the PE folks, who made a case for the superiority of PE) that PE was the way to go, and that EMDR was not going to be supported. This was part of the reason after 14 years that I transferred to the Tampa VA in early 2008.

I took a position as Military Sexual Trauma coordinator, having had experience working with men with MST at Bay Pines. The MST position at Tampa involved working with both men and women with MST, and I quickly requested that a female co-coordinator be hired, to allow for gender preference with regard to therapist. There were a few Psychologists on staff who did EMDR, and there did not seem to be quite the same polemics as were the case at Bay Pines. I was able to arrange a Part 1 and Part 2 training in EMDR through the EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Program, in July and November, 2009.

But by 2009, my interests had shifted. I had remarried, and felt reinvigorated in my personal and professional life. After attending a workshop by Bessel van der Kolk, I became inspired to learn more about neurofeedback to help in treating more difficult (developmental trauma disorder) patients, as I had found EMDR alone (with resource development exercises) to be insufficient.

By happenstance, I got interested first in LENS neurofeedback, after reading in ‘A Symphony In The Brain’ that Len Ochs had treated a combat PTSD veteran successfully with only a half dozen sessions of LENS. I attended two trainings in 2010. I realized that I was confused and didn’t really know what I was doing, and needed a solid foundation in traditional neurofeedback. As providence would have it, Rob Longo offered a workshop in July, 2010, which one of my colleagues told me about. It was life-changing. I got in touch with Dr. Soutar, and did some recommend reading, and traveled to Alpharetta, Georgia, to the Hampton Inn for my first Introduction to qEEG workshop. I volunteered for Dr. Soutar to use me as a mapping subject, and he did a mini-Q on me. As he interpreted, I was stunned by the accuracy, and felt exposed as if in my underwear. He picked up on both a past injury I had sustained to me right prefrontal area when I was three years old, as well as sequelae from the MVA in 2001. I was immediately hooked, no turning back. I ate, slept, and drank neurofeedback, taking the Advanced qEEG, Alpha-Theta workshop, AVE Entrainment workshop, and BCIA certification training workshop.

I had started writing up proposals to do research. Initially, it was based around LENS (with which I was more familiar). I spoke to a staff member in the Research and Development department at Tampa VA. He had heard of Len Ochs. He gave me some suggestions about how to go about obtaining the paperwork for writing up a formal proposal. I also spoke with one of the senior staff members who had been a collaborator with Psychological Assessment Resources (PAR; Odessa, Florida outside of Tampa) doing research with rating scales that were published by PAR. He suggested I write a proposal for a very small pilot study (N = 5), to show safety as much as efficacy, before doing bigger. Unfortunately, my Psychology Supervisor did not support Neurofeedback. He mentioned that I could submit an IRB proposal, but he was not willing to fund neurofeedback equipment (through Mental Health), nor was he willing to allow me to use my own equipment. I wrote up a proposal, but eventually gave up, realizing that there was little enthusiasm or support there.

I later learned some of the history of why Tampa VA was cold to neurofeedback. I spoke to one (perhaps two) of the senior Neuropsychologists at Tampa VA, around 2011. I asked why there seemed to be little interest in Neurofeedback, given that Tampa VA was one of only four designated VA Polytrauma centers in the US. This is the gist of his response, from my recollection: We had a guy come over here (from Bay Pines) and he did some neurofeedback (involving a computer program he developed) with some of the patients, and it didn’t work.

I later learned that this individual (who had been working at Bay Pines VA in the Research Department, during about the same time I worked at Bay Pines VA, though our paths had never crossed) was none other than Robert Thatcher, Ph.D. I had a chance to ask Dr. Thatcher about this experience myself, when he was doing a presentation at a workshop held in Sarasota in May, 2014 (on High Performance Neurofeedback, which impressed me as basically a pirated and souped-up version of LENS). Upon asking Dr. Thatcher about his past experience with neurofeedback in his collaboration with Neuropsychology staff at Tampa VA, he communicated basically that (to my recollection) the Tampa VA neuropsychologists seemed skeptically biased against neurofeedback from the start, and weren’t willing to give it a fair trial. I wish I had known this history before I had invested time and energy in developing a research proposal which went nowhere.

My wife, Sheri, and I had talked about moving away from the Florida to get away from my overbearing siblings, the punishing heat, the congestion, the noise, the traffic, and my long commute to work (at that time, I had been working at the New Port Richey VA satellite clinic, a 90 minute commute each direction, five days a week). Sheri did not want to relocate within Florida. I was offered (after interviewing) a position at the James H. Quillen (Mountain Home) VA in the Home-Based Primary Care program. It was a stressful move, but we arrived at our new home in Jonesborough, TN, in late March, 2015.

My Psychology supervisor seemed like an open-minded fellow, and I asked if he would consider allowing me to do neurofeedback. He mentioned something about a staff member having done it in the past and some problems having arisen, yet indicated that he would remain open to the possibility. He reassured me, “Let’s wait a few months, and then we will take a look to see if there is any money in the budget for some equipment.” I later learned that this was his polite Tennessean way of saying ‘No’ and deflecting away from the subject. I had also asked if it would be possible to write up a research proposal to submit to IRB, and he dismissed this as involving “too much red tape”. VA Psychologists traditionally have no ‘hands on” privileges to physically touch a patient as part of a psychotherapeutic intervention. Applying a cleaning gel to the scalp and attaching sensors, as well as all of the sterilization and hygiene issues involved, was the medical profession’s turf (essentially a medical procedure) and any proposal was likely to get bogged down in committees and go nowhere.

Fast forward to August, 2016. I saw a thread on the NewMind Listserve where a clinician mentioned having had experience using an auditory stimulation unit called the Bioacoustical Utilization Device (BAUD; Lawliss, 2006)). The clinician made the claim that that it was faster and more effective than EMDR, which got my attention. I did an internet search and looked up everything I could find about BAUD. Most of it was video from the website of Frank Lawliss, Ph.D., who (with his son) invented the BAUD device. While binaural beats had been around for awhile (since the 1970s), this device was hand-held, and used square-wave rather than sine-wave technology. The mildly noxious quality of the square wave grabs the attention of the amygdala, the brain’s emotional alarm center.

I then came across a case study example by George Lindenfeld, Ph.D., and George Rozelle, Ph.D., called “Resetting the fear switch in PTSD.” I had met George Rozelle in July of 2014. I was working for Sharon, a Nurse Practitioner in Palm Harbor, Florida, doing neurofeedback with several of her clients. Sharon was involved in a study using High Performance Neurofeedback with former NFL players, being coordinated by George Lindenfeld. He gave us a tour of his MindSpa facility on a Saturday, a state-of -the-art facility in Sarasota, Florida, catering to people who can afford to pay out of pocket for ‘state of the art’ holistic interventions (hint: rich people). George Rozelle had all kinds of gadgets, including all of the latest bells and whistles, including Brain Avatar, Neuroguide, Brain-Surfer, and High Performance Neurofeedback. His facility had a variety of practitioners. I believe there was a Hyperbaric Oxygen chamber. There was a room with a sensory deprivation tank. There was another room with a NeuroStar transmagnetic stimulation unit. And other dazzling technology and holistic interventions provided by various staff specialists. I felt like a kid in a Godiva candy store.

The case study involved qEEG brainmapping before and after a brief intervention called RESET. RESET is a method involving the very careful individualized adjustment and fine-tuning of the frequency and disruptor (offset frequency) knobs of the BAUD unit, based upon the response of each client. Once the individual settings are obtained, a 5 minute exposure trial is undertaken, during which the client is instructed to ‘light up the target (stressful memory) with all of your senses (nonverbally, intense bodily focus and awareness) while the tone is played through headphones. If the SUDS rating decreases (to the target) after the initial 5 minute trial, then additional sessions lasting 5 to 20 minutes are conducted on the disturbing memory until a minimal (and lasting) SUDS value is attained.

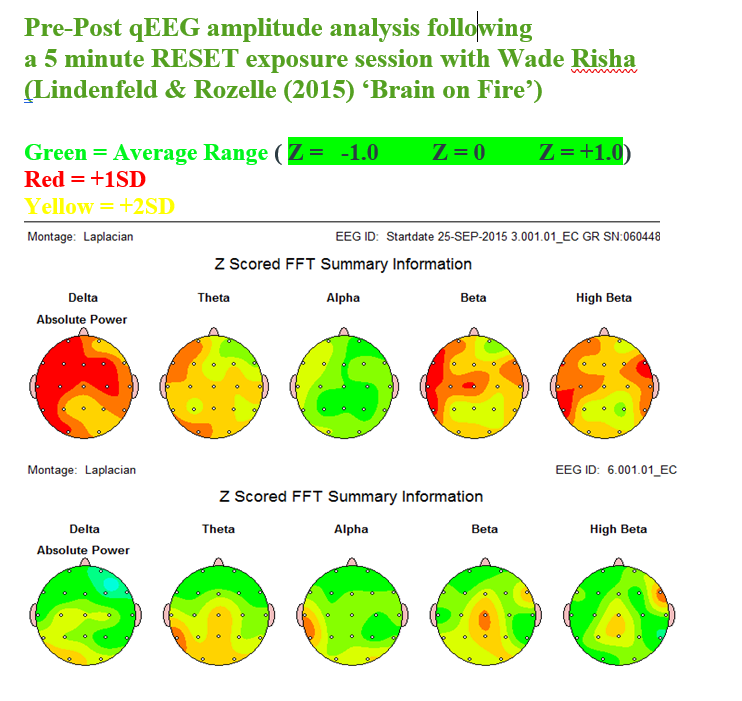

The participant was an Iraq War veteran with PTSD. Here are his (Neuroguide) pre and post qEEG brainmaps, after a 5 minute exposure trial (following the tuning process to obtain his unique settings):

My jaw dropped as I compared these two maps! This would be akin to the Peniston & Kulkowsky results, or the Bill Scott CRI-HELP results, but in a single session. I simply HAD to find out more about this method.

As luck would have it, George Lindenfeld had previously lived in Asheville, and his wife wanted to move to Florida where they could be closer to one of their daughters, Katy, a Psychologist on the east coast of Florida. George and his wife lived in Sarasota, but were vacationing in Asheville at the time I contacted him. He also had just done a television show just two weeks earlier with a Psychologist/Talk Show Host in California, about the RESET approach (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVZbR8k_7OM)

I arranged with Dr. Lindenfeld to visit him at the RV Park where he was vacationing, early afternoon of Saturday, August 6, 2016. My wife, Sheri, drove, while I read Chapter 4 (provided by Dr. Lindenfeld) from his second book about RESET written for the clinician, along with a case study he had done on Fibromyalgia. When I arrived, we went to the empty recreation hall, where we spent the next two hours. I hired him to do a one-hour session at his customary fee, using RESET to address a very visceral/somatic and minimally verbal past traumatic memory from when I was 15 years of age – a memory than was not aided by EMDR, or even Alpha-Theta neurofeedback.

Dr. Lindenfeld encouraged me remain skeptical, while he systematically guided me through adjusting the volume for the two channels, then adjusted two different tones based upon my response. To the first tone (frequency), he asked me to light up the target (trauma memory) nonverbally (without disclosure) with all of my senses, and to hand signal when the tone ‘resonated’ with the subjective bodily sensations. Selecting that base tone, he asked me to light up the target again, while he added a second, slightly higher tone in the left ear. My job was to hand signal when I experienced a fading of the bodily sensations, or calming effect. Once he had these settings, he fine tuned them by doing a second round of tuning where he used an ideomotor signaling technique (similar to one sometimes used in hypnosis). Once he had the desired settings (based upon my physiological response), it was time to do a 5 minute trial to see whether or not the settings were effective in lowering the SUDS associated with the target sensations.

He played the tone combination while I lit up the target as intensely as I could, grimacing in aversive pain, wringing my hands, grunting, breathing heavily and rapidly, and sweating. It probably looked dramatic to an observer, but it was me really getting into a memory that I absolutely hated to revisit. I wanted to be rid of this useless and disturbing memory, once and for all, yet I had doubts that it could ever be changed. The subjective experience was intense, and different from other interventions. If EMDR is a high speed train going from stop to stop, RESET is a roller coaster- rotor rooter, rapidly swirling and drilling downward into the core emotions and bodily aspects of the memory, then magically erasing some of the intrusive and aversive quality (my SUDS went from a 9 to a 4 and stayed there). I used the settings Dr. Lindenfeld had come up with on my own BAUD device that I had purchased, and within two sessions lowered the SUDS to a realistic 2. In just the same manner I had been ‘hooked’ when Dr. Soutar interpreted my miniQ map, and hooked on the calm-connected- compassionate feeling I experienced after my first Alpha-Theta workshop, I became instantly hooked on RESET. RESET doesn’t leave a person with the nice pleasant feeling afterward that Alpha Theta and EMDR do. It is a rough roller coaster which for me involved waves of high arousal followed by brief calm – sort of like the driving in Florida under a storm cloud and downpour, entering a sunny area where the rain is drying up, and going through this pattern a couple of times in the span of just a few minutes. Instead, I was emotionally and physically spent, but utterly relieved that toxic material had forever been removed from my psyche, and euphoric about the magic that had just transpired and the possibilities it raised.

I kept in touch with Dr. Lindenfeld, and in September of 2018, I had the rare opportunity to undergo 3 training days with him (on consecutive Saturdays, 6 hours of training each session) in RESET. There were important aspects of the method that I had forgotten or not closely attended to (having been in the hot seat), and now learned how to administer RESET. RESET is an interactive method for getting the maximum effectiveness out of the BAUD unit for each person, instead of a cookbook approach. PTSD is not a do-it-yourself; one cannot be the driver and at the same time immersed in the experience of being the passenger.

To say that I was enthusiastic about this new method is an understatement. I tried it out with some volunteers with some very good results. It did not work with everyone, but it worked about 85% of the time. About 50% have an instant response in one session, and the goal is to keep working on the memory to lower the SUDS, using 5 to 20 minutes of exposure (pairing tones played through headphones with lighting up the target). About 35% seem to have a delayed response, report a positive development a couple of days later. Another 10 to 15% are either too highly anxious, and/or unable to discern subtle changes in their bodies, and have no response.

I contacted the Research and Development committee at Mountain Home VA, and got guidance on the process. The forms and IRB process was done by East Tennessee State University. I had to complete an online training course with CITI (based in Miami, FL) on ethics and procedures in doing research, which took no less than 10 hours to complete. I worked on the 45 to 50 page submission form, which included numerous forms (procedural and other) which had to be attached. I estimate that I spent 100 hours writing up a proposal, then coming back and doing a substantial revision of it after getting feedback about procedures of safe data storage and related issues from another R&D staff member. The revision probably took another 80 hours. The study was a step by step procedure for doing preassessment, then 4-5 sessions of RESET, then post-assessment. I had to explicate all of the steps that would be taken (without deviating from them) if there were adverse effects, complications, and following up with participants. I had to explicate the screening process, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. I was using questionnaire and performance based psychological/neuropsychological assessment instruments with participants, as well as asking collaterals (spouse) to complete rating scales. I had to detail how the study would contribute, and the justification for using human subjects, and come up with an exhaustive list of possible unintended negative effects and how these would be dealt with. It was a massive undertaking.

When it was finished, I asked my supervisor to review and sign off on it. She would not do so without the approval of the Chief of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences (John). John did not answer email messages unless it was something of immediate importance to him. My reasoning is that since I modified that RESET procedure to where there was no physical contact with the equipment and disposable headphones could be used, it would reduce any red tape. A picnic was going on, and John was doing some of the cooking (May, 2019) and I went there in person and asked him if he would take a look at it. He said that he would, and then I never heard anything back. His non-response was a “No.” I was extremely disappointed, if not a bit demoralized, to have spent so much time and effort trying to do something positive to help veterans in the future, only to have the Chief of Mental Health completely ignore it.

One of the unintended negative consequences of trying to introduce new things into a resistant system such as the VA is that over time one gets a reputation (from administration) as being a nonconformist, someone who pushes the boundaries, and not someone you want in a position of leadership or responsibility. And somehow, that reputation seems to follow you, even when you transfer to other facilities. The ideal employee is one who does everything he or she is asked to do, does it expediently, does not complain or question authority, does not create any problems, and doesn’t ask for anything.

What are the alternatives to the VA, with regard to introducing neurofeedback in places where it is needed?

How and where can we introduce neurofeedback in a manner in which it is likely to be accepted? There is no easy solution or option. However, I have some ideas.

I believe that if one were to work or volunteer part-time for a nonprofit agency, it would be important for a trust and confidence to have been earned, before starting to talk about neurofeedback as an option. I have lost job possibilities by talking about neurofeedback far too early in the process. I have lost other options by being too passionate, and trying to sell it too quickly. Patience is necessary in planting seeds. Each successful case is a seed that has grown into a flowering success. People have to witness the success by observation of the seemingly miraculous transformation of an individual, or to have experienced the positive changes personally, in order to believe it. The world is an ultra-cautious place. Don’t make technology the main focus. Relationships need to come first, before technology. A sales pitch rarely works, if ever. Neurofeedback gets known mostly by word of mouth, not by pontification or advertisement.

One potential option is to write a grant proposal. Do searches to find out what types of grants are available and the issues to which the grants pertain. For example, there are high rates of PTSD among first responders: ER nurses, physicians, paramedics, fire fighters, and police have high rates, even when there isn’t a pandemic. Police departments often hire military veterans, many of whom have some degree of underlying PTSD (from highly stressful childhood and or military experiences) that they are able to keep concealed (for a while).

As we know, there is the fight version (sympathetic overarousal/approach), the flight version (sympathetic overarousal/avoid), and the freeze versions (both sympathetic and parasympathetic aspects) of PTSD. Police officers (and prison guards) are faced with PTSD as an occupational hazard. To admit that one has PTSD and to seek help for PTSD is taboo– a weakness, a letdown of one’s fellow officers, and a risk for being ascribe a ‘profile.’ A profile is the kiss of death for one’s career, according to police I have spoken to who have been willing to confide. The modern police officer is in a dilemma: Seek help and risk one’s career and status, or just keep and stay under the radar and suffer the consequences. We know all too well that demoralization, addictive behaviors, marital problems, and even domestic violence are prevalent among under-treated PTSD populations, including the police.

Churches and synagogues are another avenue. If one can find a pastor or rabbi who knows of a person who needs help and support (not only spiritually, but emotionally), a success may help pave the way for you to present at a church-sponsored celebrate recovery group, or grief support group. At that point, church elders or clergy will view you as a trusted professional resource for their congregations.

If you would like any additional information about the VA, please email me. I want to share my experiences and knowledge to help the next generation(s) of practitioners.

REFERENCES

Applied Neuroscience International, Inc. – Most affordable EEG & QEEG Analysis and Neurofeedback Software. https://appliedneuroscience.com/

Bell, Ashlie (2017, March ) Tuning the Traumatized Brain: A systematic review of the literature on Neurofeedback for PTSD. Poster presentation at the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB).

Benson, A., and Ladou, T. W. (2016). The use of neurofeedback for combat veterans with neurofeedback. In H.W. Kirk (Ed.), Restoring the Brain: Neurofeedback as an integrative approach to health, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 181-200

Bourne, D., Hefland, M., et. al. (2017). Evidence Brief: Effectiveness of Stellate Ganglion Block for Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Resource and Human Development. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323840137

Buckley, T. C., & Kaloupek, D. G. (2001). A meta-analytic examination of basal cardiovascular activity in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 585-594.

Butt, M., Espinal, E., Aupperle, R. L., Nikulina, V, & Stewart, J. L. (2020) The Electrical Aftermath: Brain Signals of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Filtered Through a Clinical Lens. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 368. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00368. eCollection 2019

CBS News 60 minutes (2019, June 16) SGB: A possible breakthrough treatment for PTSD: A simple shot in the neck could put PTSD sufferers on the path to recovery, by Bill Whitaker. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/sgb-a-possible– breakthrough-treatment-for-ptsd-60-minutes-2019-06-16/

Chalmers, J. A., Quintana, D. S., Abbott, M. J., & Kemp, A. H. (2014). Anxiety disorders are associated with reduced heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, 1-11.

Currie, C. L., Remley, T. P., & Craigen, L. (2014). Treating trauma survivors with Neurofeedback: A grounded theory study. Neuroregulation, 1, 219-239.

Curtois, C. A., Sonis, J., Brown, L.S., Cook, J., Fairbank, J.A., Friedman, M., Gone, J.P., Jones, R., LaGreca, A., Mellman, T., Roberts, J., Schulz, P., Bufka, L.F., Halfond, R., & Kurtzman, H. (2017). Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults, American Psychological Association. Washington DC: APA Press.

Dahl, Monica G. (2016). PTSD symptom reduction with neurofeedback. In H.W. Kirk (Ed.), Restoring the Brain: Neurofeedback as an integrative approach to health, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 201-230.

Dennis, P.A., Dedert, E., Van Voorjees, E. E., and Beckman, J. C. (2016). Examining the crux of autonomic dysfunction in PTSD: Whether chronic or situational distress underlies elevated heart rate variability, Psychosomatic Medicine, 78, 805-809.

Dreis, S. M., Gouger, A. M., Perez, E. G., Russo, M., Fitzsimmons, M. A., & Jones, M. S. (2015). Using Neurofeedback to lower anxiety symptoms using individualized QEEG protocols: A pilot study. Neuroregulation, 2, 1-10.

Foa, E., Hembree, E, & Rothbaum, B. (2007). Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences: Therapist Guide (Treatments That Work). New York: Oxford University Press).

Forman-Hoffman, V., Middleton, J. C., Feltner, C., Gaynes, B. N., Weber, R. P., Bann, C., Viswanathan, M., Lohr, K. N., Baker, C., & Green, J. (2017). Psychological and Pharmological Treatments for Adults with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systemic Review Update. Prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD.

Foster, D., & Thatcher, R. (2015). Surface and LORETA neurofeedback in the treatment of post- traumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. In R. W. Thatcher and J. F. Lubar (Eds), Z-score neurofeedback: Clinical applications, 59-92.

Gapen, M., van der Kolk, B. A., Hamlin, E. D., & Hirshberg, L., (2016). A pilot study of neurofeedback for chronic PTSD. Applied Psychophysiology and Neurofeedback, 40, 1-11.

Gerin, M. I., Fichtenholtz, H., Roy, A., Walsh, C. J., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S., & Hampson, M. (2016). Real-time fMRI Neurofeedback with war veterans with chronic PTSD: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, 1-11.

Hanling SR, Hickey A, Lesnik I, et al. (2016) Stellate Ganglion Block for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 41, 494–500. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27187898

Hanling, S., Fowler, I. A., Hackworth, R. J. (2017) Stellate Ganglion Block for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Call for Clinical Caution and Continued Research https://www.asra.com/asra– news/article/110/stellate-ganglion-block-for-posttraumati

Hickling, E.J., Sison, G. F. P. & Vanderploeg, R. D. (1986). The treatment of previous term post-traumatic stress disorder with biofeedback next term and relaxation training. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 11, 125–134.

Jones. M. S, & Hitsman, H. (2018). QEEG-guided neurofeedback treatment for anxiety systems. Neuroregulation,5, 85-92.

Kibler, J. L. (2009). Posttraumatic stress and cardiovascular disease risk. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 10, 135-150

Lake, James H. (2015) The integrative management of PTSD: A review of conventional and CAM approaches used to prevent and treat PTSD with emphasis on military personnel. Advances in Integrative Medicine, 2, 13-23.

Lande, R. G., Williams, L. B., Francis, J. L., Gragnani, C., Morin, M. L., et. al. (2010). Efficacy of biofeedback for post-traumatic stress disorder, Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 18, 256-259.

Lawlis, F., (2006) About the BAUD. http://www.baudtherapy.com/about.html

Lindenfeld, G. L., Rozelle, G., Hummer, J., Sutherland, M. R., & Miller, J. C. (2019a). Remediation of PTSD in a Combat Veteran: A Case Study. NeuroRegulation, 6(2), 102-125. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.2.102

Lindenfeld, G., Rozelle, G., Soutar, R., Hummer, J, & Sutherland, M. (2019b). Post-traumatic stress remediated: A study of eight combat veterans. New Mind Journal: Winter, 2019, www.nmindjournal.com

Lindenfeld, G., & Bruursema, L. R. (2015). Resetting the Fear Switch in PTSD: A Novel Treatment Using Acoustical Neuromodulation to Modify Memory Reconsolidation. http://www.academia.edu/12683048/Resetting_the_Fear_Switch_in_PTSD_A_Novel_Treatment_Using_Acoustical_Neuromodulation_to_Modify_Memory_Reconsolidation

Lipov, E. G., Joshi, J. R., Sanders, S., & Slavin, K. V. (2009). A unifying theory linking the prolonged efficacy of the stellate ganglion block for the treatment of chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS), hot flashes, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Medical Hypotheses, 72(6), 657–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.01.009

Lipov, E.G., Navaie, M., et. al. (2012). A Novel Application of Stellate Ganglion Block: Preliminary Observations for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Military Medicine, 177, 125.

Lipov, E. (2017, November) To the Editor: Stellate Ganglion Block for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Call for the Complete Story, and Continued Research. Newsletter of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medication. https://www.asra.com/asra-news/article/92/to-the-editor-stellate-ganglion-block-fo

Lipov, E., Tukan, A., & Candido, K. (2018). It Is Time to Look for New Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Can Sympathetic System Modulation Be an Answer? Biological Psychiatry, 84(2), e17–e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.07.026

McCune, T. R. (2016). Heart rate variability: Pre-deployment predictor of post-deployment PTSD symptoms. Biological Psychology,121,91-98.

McReynolds, C. J., Bell, J., & Lincourt, T. M. (2017). Neurofeedback: A non-invasive treatment for symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in veterans. Neuroregulation, 4, 114-124.

Mulvaney, S.W., Lynch, J.H., Hickey, M. J., Rahman-Rawlins, T, Schroeder, M., Kane, S., & Lipov, E. (2014). Stellate ganglion block used to treat symptoms associated with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: a case series of 166 patients. Military Medicine, 179, 1133-1140. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25269132

Mulvaney, S. W., Lynch, J. H., Kotwal, R. S., (2015) Clinical Guidelines for Stellate Ganglion Block to Treat Anxiety Associated With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. – PubMed – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26125169

Navaie, M., Keefe, M. S., Hickey, A., Mclay, R. N., Ritchie, E., & Abdi, S. (2014). Use of Stellate Ganglion Block for Refractory Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of Published Cases. Journal of Anesthesia and Clinical Research, 5. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6148.1000403

Nagpal, M. L., Geichauf, K., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2013). Meta-analysis of heart rate variability as a psychophysiological indicator of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Trauma and Treatment, 3, 1-10.

Nelson, D. V., & Esty, M. L. (2012). Neurotherapy of traumatic brain injury/posttraumatic stress symptoms in OEF/OIF veterans. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24, 237-240.

Nicholson, A. A., Rabellino, D., Densmore, M., Frewan, P. A., Paret, C., Kluetsch, R., Schmahl, C., Theberge, J., Neufeld, R. W. J., McKinnon, M. C., Reiss, J., Jetley, R. & Lanius, R. A. (2017). The neurobiology of emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Amygdala downregulation via real-time fMRI neurofeedback. Human Brain Mapping, 38, 541-560

Noohi, S., Miraghaie, A.M., Arabi, A., & Nooripour, R. (2017). Effectiveness of neuro-feedback with alpha/theta method on PTSD symptoms and their executing function. Biomedical Research, 28, 1-13.

Omstead, K.L.R., Bartoszek, M., et. al (2020). Effect of Stellate Ganglion Block Treatment on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA-Psychiatry, 77(2), 130-138. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3474

Othmer, S (2010). Psychological Health and Neurofeedback: Remediating PTSD and TBI. EEG Info., Woodling Hills, California, 1-62.

Orndorff-Plunkett, F., Singh, F., Aragon, O.R., & Pineda, J.A. (2017). Assessing the effectiveness of Neurofeedback Training in the context of clinical and social neuroscience. Brain Science, 7, 1-22.

Orr, S. P., Metzger, L.J., Lasko, N. B., Macklin, M. L., Peri, T., & Pitman, R. K. (2000). De novo conditioning in trauma- exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 290-298.

Orr, S. P., Meyerhoff, J. L., Edward, J. V., & Pitman, R. K. (1998). Heart rate and blood pressure resting levels and responses to generic stressors in Vietnam Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 155-164.

Panisch, L.S., & Hai, A. H. (2018). The effectiveness of using Neurofeedback in the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, DOI: 10.1177/1524838018781103

Peniston, E.G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1991) Alpha-theta brainwave neuro-feedback therapy for Vietnam veterans with combat- related post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Psychotherapy, 4, 47–60.

Peniston, E. G., Marrinan, D. A., Deming, W.A., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1993) EEG alpha-theta brainwave synchronization in Vietnam theater veterans with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse. Medical Psychotherapy: An International Journal, 6, 37–50.

Peterson, K., Bourne, D., Anderson, J., Mackey, K., & Helfand, M. (2017). Evidence Brief: Effectiveness of Stellate Ganglion Block for Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323840137

Polak, A. R., Witteveen, A. B., Denys, D., & Olff, M. (2015). Breathing biofeedback as an adjunct to exposure in cognitive behavioral therapy hastens the reduction of PTSD symptoms : A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiological Biofeedback, 40, 25-31.

Powers, M. B., Halpern, J. M., Ferenschak, M. P., Gillihan, S. J., & Foa, E. B. (2013). A meta-analytic review of Prolonged Exposure for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 10, 428 – 436.

Putman, J. (2000). The effects of brief, eyes-open Alpha brain wave training with audio and video relaxation induction on the EEG of 77 Army reservists. Journal of Neurotherapy, 4, 17-28.

Pyne, J.M., Constans, J.I., Wiederhold, M.D., Gibson, D. P., Kimbrell, T., Kramer, T. L., Pitcock, J. A., Han, X., Williams, D. K., Chartrand, D., Gevirts R.N., Spira, J., Wiederhold, B. K., McCraty, R., & McCune, T.R. (2016). Heart rate variability: Pre-deployment predictor of post-deployment PTSD symptoms. Biological Psychology, 121, 91-98.

Rastegar, N., Dolatshahi, B. & Dogahe, E. R. (2016). The effect of neurofeedback training on increasing sustained attention in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology, 4, 97-104.

Resick, P.A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1993). Cognitive Processing Therapy for Rape Victims: A Treatment Manual (Interpersonal Violence: The Practice Series), London, England: Sage Publications.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016) Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual, 1st Edition. New York: The Guilford Press.

Reiter, K. Anderson, S.B., & Carlsson, J. (2016) Neurofeedback Treatment and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Effectiveness of Neurofeedback on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the Optimal Choice of Protocol. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorder,204, 67-77.

Scott, W. D., Kaiser, D., Othmer, S., & Sideroff, S. I. (2005) Effects of an EEG Biofeedback Protocol on a mixed substance abusing population. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31, 455-469.

Shapiro, F. (2008). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy, Third Edition: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. New York: The Guilford Press

Smith, W. D. (2008) The effect of neurofeedback training on PTSD symptoms of depression and attention problems among military veterans. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Steenkamp, M. M., Litz, B.T., Hoge, C. W., & Marmar, C. R. (2014) Psychotherapy for Military- Related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of the American Medical Association, 314, 489-500.

Steingrimsson S, Bilonic G, Ekelund AC, Larson T, Stadig I, Svensson M, Vukovic IS, Wartenberg C, Wrede O, & Bernhardsson S. (2020). Electroencephalography-based neurofeedback as treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 63(1), 1-12. :e7. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.7.

Tan, G., Dao, T. K., Farmer, L., Sutherland, R.J., & Gevirtz, R. (2011). Heart rate variability (HRV) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36, 27-35.

Tan, G., Wang, P., & Ginsberg, J. (2013). Heart rate variability and posttraumatic stress disorder, Biofeedback, 41, 131-135.

Tran, K., Moulton, K., Santesso, N., & Rabb, D. (2016). Cognitive Processing Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; CADTH Health Technology AssessmentsHYPERLINK “https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/n/cadthhtacollect/”.

Trudeau, D. L (2000). The treatment of addictive disorders by brain wave biofeedback: A review and suggestions for future research. Clinical Electroencephalography, 31, 13-22.

Wahbeh, H., & Oken. B. S. (2013). Peak high-frequency HRV and peak alpha frequency higher in PTSD. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback, 38, 57-69.

Walker, J. E. (2009). Anxiety associated with post traumatic stress disorder- the role of quantitative electro-encephalograph in diagnosis and in guiding neurofeedback training to remediate anxiety, Biofeedback, 37, 67-70.

White, E. K., Groeneveld, K. M., Tittle, R.K., Bolhuis, N. A., Martin, R. E., Royer, T. G., & Fotuhi, M. (2017). Combined Neurofeedback and Heart Rate Variability training for individuals with symptoms of anxiety and depression: A retrospective study. Neuroregulation, 4, 37-55. Wigton, N. L., & Krigbaum, G. (2015). A review of QEEG-guided Neurofeedback. Neuroregulation, 2, 140-155.