Anxiety and Perfectionism have a strong relationship as previously documented in Findings 1. As a clinical observation, we noted that Competitiveness was usually elevated alongside of Perfectionism when higher Depression scores were present. To begin evaluating this hypothesis, we inspected the Level of Competitive scores when compared to high Depression scores and high Anxiety scores. Our peak performers typically averaged a Competitive score of 12 on the ISI. Drawing a sample of n = 2381 from the NM Database we found the average score for those who are not peak performers, but instead have high levels of Anxiety, had mean Competitive scores of 17.7. Those who had high Depression scores of 25-30 (n = 82), interestingly enough, had mean Competitive scores of 17.9 (N= 2381). So both High levels of Anxiety and Depression were associated with higher levels of Competitiveness than peak performers.

When looking at the relationship between Anxiety and Competitiveness, it was observed that those with moderate Anxiety also had lower mean Competitive scores of 16 versus the high Anxiety group mentioned above having a score of 17.7. Those with subclinical Anxiety had mean Competitive scores of 15.8 and those reporting minimal symptoms of Anxiety had mean Competitive scores of 15. So clearly the more Competitive individuals are, the more Anxious they are likely to be or vice versa. In addition we can surmise that the higher the Anxiety score the more likely we are to find both elevated Depression and elevated Competitiveness. Also recall, In the previous analysis it was reported that those with moderate anxiety tended to have fewer features of depression than those with higher anxiety scores. The question remains, does the trait or behavior result in Anxiety or does Anxiety result in the development of the behavior.

In previous analyses during the development of the ISI, we found the average scores for peak performers in the dimension of Competitiveness is 12 and their depression scores are below 10. This indicates that there is a healthy level of competitiveness in peak performers but excess Competitiveness is more likely a sign of previous toxic stress in childhood (Shonkoff & Garner, 2011). Competition can be associated with activities related to a wide range of psychological and social resources. The present research tells us that Toxic Stress is derived from a failure of emotional support during critical periods of social distress. The Complex Trauma model is defined in the same manner. According to most of the research dating back to the mid twentieth century, this low support environment generates a loss of trust in others and self-worth. In fact many longitudinal studies indicate that emotional abandonment is more devastating to human children than physical abuse.

Noting that Perfectionism and Competitiveness were high in Depressed and Anxious individuals, we questioned them regarding their Perfectionism and the role that it played in their daily life. This added an important qualitative feature to our data gathering. For many, paying attention to details was insurance against making errors in behavior that would cost them in terms of security and safety as well as reduce conflict and enhance attention with appreciation from parents and peers. At the same time, the effort seemed to reinforce the feeling that they were not especially competent in their daily activities and possibly defective. Verbal and emotional abuse seemed to enhance this experience. Perfectionism was then a means to an end as well as an ongoing measure of their personal value. Perform better and gain love and appreciation.

The question arose at this juncture : If these individfuals were perfectionistic, did this enhance their awareness in the deficits of others, and did they see the errors in others as deficits which impeded their own efforts to maintain control and achieve appreciation? The complexity escalates at this point in the analysis. Hypervigilence, a key physiological feature of anxiety, alters the social experience at the sensory level as well as the processing level. We know fear alters the perceptual field, sometimes aligning disparate sensory objects activities into apparently meaningful patterns that may or may not exist as a potential threat. Most of our clients indicated that their perfectionism was oriented more toward keeping them safe and avoiding conflict rather than leading to derogation activities with regard to others. However, in extreme cases one could imagine how this line of action could lead to extreme processing errors as in personalities disorders where the perceived threatening activity of others is highly personalized as a threat to their safety. When this activity is ubiquitous, then everyone is a potential threat and not to be trusted. This would only enhance isolation and a very elevated sense of external locus of control.

When asked if they felt a need to perform better than others or if they expected more from others due to their Perfectionism, they replied that it was a need to perform better than others driven by a fear that they were not as good as others and may not have equal access to resources. At more intense levels they felt despair and hopeless.

In relating this to the family system and the level of emotional support it provided, we asked if they felt their parents were highly critical of them or if they failed to measure up to their parent’s expectations. In most cases they responded that they felt they were deficient or defective in some way and could not live up to expectations. Some reported that their parents were verbally critical of them on an ongoing basis. Others derived their conclusions from either the level of verbal or physical abuse or outright disregard for their feelings and/or emotional and/or physical abandonment. In this case Competitive seemed to covary with a chronic emotional experience of failure and a self-evaluation process that concluded in an estimation that they were fundamentally defective.

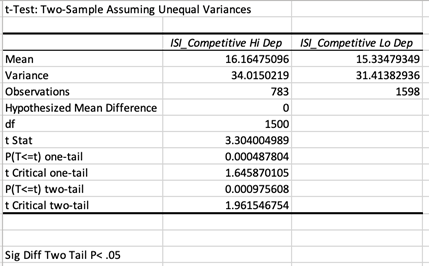

To investigate further, we drew a sample of clinical cases from the ISI data with an N = 2381 and compared two groups defined as follows: One group had high depression scores (Hi Dep) and one group had low depression scores (Lo Dep). The depression scale ranges from 1 to 30 points. We defined those with clinically significant depression (Hi Dep) as those scoring above 18 based on previous statistical analysis (Soutar, 2017?.) and those with scores between 6 to 17 as subclinical or normal (Lo Dep). Our goal was to see if those with clinical depression N = 783 had mean scores in Competitiveness that were significantly different from those who did not have clinical depression N = 1598. The analysis indicated that the two groups proved to be significantly different with respect to levels of Competitiveness at not only the .05 level but also the .01 level. Our clinical observations appear to be confirmed.

At the beginning of this set of Finings we reported that Competitiveness varied with levels of Anxiety. Having established that high and low Depression groups differ with respect to Competitiveness, the question arises regarding whether they vary over the range of Depression. To answer this question we divided the groups into various ranges of Depression. This results in the findings that those with High Depression (N =82) with scores in the range of 25-30 have mean competitive scores of 17.9. Those with Moderate Depression (N = 330) with scores in the range of 20 – 25 have mean competitive Scores of 16.1. Those with Lo Depression ( N = 362) with scores in the range of 10 – 18 have mean competitive scores of 15. Those with No Depression (N = 354) with scores in the range from 6-10 have a mean Competitive Scores of 14.2.

Based on these findings, it was concluded that Competitiveness increased incrementally with Depression when measured by the ISI and that it is likely related to managing negative self attributions.

As a final foot note

The average Perfectionism score for peak performers in the ISI is 16. For those in the High Depression group the average Perfectionism score was 22.2 (N=95). For those in the Moderate Depression group the average Perfectionism score was 20.6 (N = ?).

This suggests that as Perfectionism decreases, so does Depression (N=330).

References

Shonkoff, J.P., Garner, A. S. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics,129 (1), e232-e246. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Soutar, R. (2017). Asymmetry as a reliable measure of adult anxiety and depression. New Mind Journal. Fall 1-4.